Obituary by Mukunda Rao

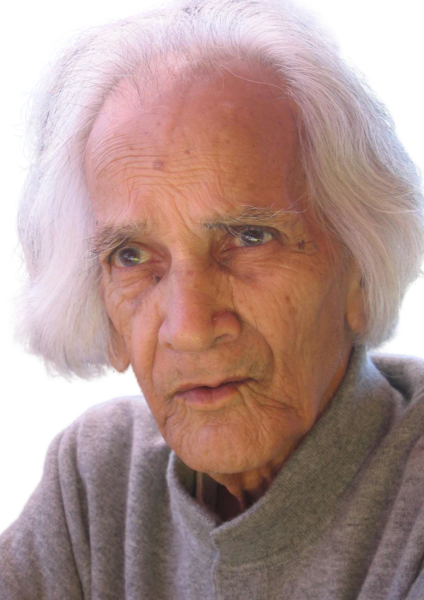

Remembering U.G. Krishnamurti

U.G. Krishnamurti, lovingly called UG by his friends and admirers all over the world, is no more. The end came on 22 March 2007 at 2.30 pm at the villa of his friend, in Vallecrosia, Italy. As per U.G.Krishnamurti’s advice, with no rituals or funeral rites, the cremation was carried out the next day at 2.45 pm, in Vallecrosia, Italy. He was eighty-nine years old. UG is survived by his erstwhile family, comprising his two daughters, Usha and Bharati, and their respective families and his son, Kumar and his family. But his actual family is much larger than that, extending over the entire globe and consisting of numerous ‘friends’ to whom he has been closer than their own families and indeed their own selves. Seven weeks before, UG had a fall and injured himself.

This was the second such occurrence in two years. He did not want such an incident to occur once again which would make him further dependent on his friends for his daily maintenance. Seven weeks before, UG had a fall and injured himself. This was the second such occurrence in two years. He did not want such an incident to occur once again which would make him further dependent on his friends for his daily maintenance. So he refused medical or other external intervention. He decided to let his body take its own natural course. He was confined to bed and his consumption of food and water became infrequent and then ceased altogether. ‘It’s time to go,’ he declared, joined his palms in namaste, thanked his friends and advised them to return to their places. Only his longtime friends, the filmmaker, Mahesh Bhatt, Larry and Susan Morris, and few other friends stayed back to guard his body and do whatever was necessary when the end came. UG did not die of any disease, although he suffered from ‘cardio-spasm’ for many years, which became quite severe in the last days of his life.

UG did not show the slightest signs of worry or fear about death or concern for his body even at the end of his life. He did not leave any specific instructions as to how to dispose of his dead body. ‘You can throw it on the garbage heap, as far as I am concerned,’ he often would say.

Responding to questions on death, UG said, ‘Life and death cannot be separated. When what you call clinical death takes place, the body breaks itself into its constituent elements and that provides the basis for the continuity of life. In that sense the body is immortal.’

*

UG was born on 9 July 1918, in a Telugu-speaking Brahmin family in Masulipatam, a coastal town in the state of Andhra Pradesh. He lost his mother when he was seven days old and was brought up by his maternal grandfather, who was a noted, wealthy lawyer and a prominent member of the Theosophical Society. UG grew up in a peculiar milieu of Theosophy and orthodox Hindu religious beliefs and practices. Even as a boy he was a rebel yet brutally honest with whatever he did.

He did his schooling in the town of Gudivada and then his B.A. Honours Course in Philosophy and Psychology at Madras University. But the study of the various philosophical systems and Western psychology made very little impression on him. ‘Where is this mind these chaps have been talking about?’ he once asked his Psychology teacher. It was something extraordinary coming from a student who was hardly twenty years old, particularly when Freud’s ideas were considered to be the last word on human mind.

Between 14 and 21 years of age, UG spent seven years off and on with Swami Sivananda in Rishikesh practicing yoga and meditation. He had various mystical visions and experiences there, but he questioned their validity as he thought that he could recognize them only on the basis of his prior knowledge he already had about them.

In 1939, when UG was 21 years of age, he went and met Sri Ramana Maharshi and asked him, ‘This thing called moksha, can you give it to me?’ Ramana reply, ‘I can give it, but can you take it?’ struck him like a ‘thunderbolt’ and set him up on a relentless search for truth that ended at the age of 49 with a totally unforeseen result.

After leaving the university, UG joined the Theosophical Society as a lecturer and toured the country giving talks on Theosophy. Even after his marriage to Kusuma Kumari in 1943, he continued to work with the Theosophical Society and gave lectures in European countries, until, in 1953, he realized that what he was doing was not something true to his real self and quit the post in disgust. After that, he met J. Krishnamurti, who was by then famous as an unconventional spiritual teacher. For two years, he met him now and again and got into fierce discussions on spiritual matters, but later on, he was to reject JK’s philosophy, calling it a ‘bogus chartered journey.’

During this period, UG also underwent a life-altering, mystical experience, what he sometimes called a ‘death experience’. But he ‘brushed it all aside’ as of no importance and moved on, further probing and testing and questioning every experience until he came into his own.

In 1955, UG went to America with his family to get medical treatment for his son’s polio condition. When his resources began to diminish, he took to lecturing for a fee. He gave talks on the major religions and philosophies of the world and soon came to be recognized as a fine teacher from India. But, as it happened before, at the end of the second year, he lost interest in lecturing and then the inevitable happened. His seventeen years of marriage came to an end. His wife returned to India with the children. And UG drifted from one thing to another. After his aimless wanderings in London and Paris, like a dry leaf blown here, there and everywhere, he landed in Geneva and at last found refuge in Valentine de Kerven’s chalet in Saanen. By then incredible experiences had started to happen to him and his body was ‘like rice chaff burning inside’. It was a prelude to his ‘clinical death’ on his forty-ninth birthday (in 1967) and the beginning of the most incredible bodily changes and experiences that would catapult him into a state that is difficult to understand within the framework of our hitherto known mystical or enlightenment traditions. For seven days, seven bewildering physical changes took place and he landed in what he calls the ‘Natural State’. It was a cellular revolution, a full-scale biological mutation.

In 1972, UG gave his first public talk at the Indian Institute of World Culture, Bangalore. He never again gave any public talk. But he did not/could not stop people from meeting and talking to him. He responded to their queries and answered their questions in the way only he could. He usually stayed with friends or in small rented apartments, but never stayed in one place for more than six months. He gave no lectures or discourses. He had no organization, no office, no secretary, and no fixed address. Despite his endless repetition that he had ‘no message for mankind,’ ironically yet naturally thousands of people the world-over felt otherwise and flocked to see and listen to his ‘anti-teaching’. The first book, The Mystique of Enlightenment—The unrational ideas of a man called UG, put together by Rodney Arms, appeared in 1982. In 1986, he went public and gave his first TV interview, which was soon to be followed by several TV and radio interviews the world over. And UG made publishing history by not allowing copyright on any of his books saying, ‘My teaching, if that is the word you want to use, has no copyright. You are free to reproduce, distribute, interpret, misinterpret, distort, garble, do what you like, even claim authorship, without my consent or the permission of anybody.’

In the last seven years during his stay in Bangalore, he rarely engaged in serious conversations; rather he started to do something else other than answer tiresome questions, for he found all questions (except in the technical area, which is something else) were variations of basically the same question revolving around the ideas of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’. There used to be long stretches of utter silence. It used to be embarrassing; also a tremendous relief from the burden of knowing. And then UG would start playing his enigmatic little ‘games’, or invite friends to sing, dance, or share jokes. And the room would explode with laughter: funny, silly, dark, and apocalyptic! At last freed from the tyranny of knowledge, beauty, goodness, truth, and God, we would all mock and laugh at everything, mock heroes and lovers, thinkers and politicians, scientists and thieves, kings and sages, including UG and ourselves!

Who was this UG? What kind of person was he? He was the most enigmatic person you could ever meet – at once kind and cruel, most loving yet stern, constantly talking about money, seeming to ‘extract’ it from friends, yet most generous in giving; seemingly abusive and punishing, yet showering affection on the same person the next moment; utterly carefree, yet worrying about what might happen to the person in front of him; directing people to act in specific ways, yet instantly accepting of any outcome; demonstrating the most incisive logic, yet making utterly contradictory statements. For a man who complained that we are constantly preoccupied with something other than what is happening at the moment, he endlessly talked about himself and his past. One could never fathom UG’s true intentions behind his statements or actions.

His answers to our questions came straight like arrows, unsettling our minds. He was well-known for striking down not only the edifices we have so carefully built in our own minds but the foundations of human thought as a whole. UG was truly enigmatic, subversive and revolutionary, and totally fearless.

There was a unique energy with UG: in speech or in stillness it was constant and vibrant, and had a profound effect on those who were around him.

And let this be told: when UG rejected the notion of soul or atman and declared that our search for permanence was the cause of our suffering, he sounded like the Buddha; when he blasted all spiritual discourses as ‘poppycock’ and thrashed the spiritual masters as ‘misguided fools’, we thought of the fiery and abusive words of the great 9th century mystic of China, Rinzai Gigen, who declared, ‘I have no dharma to give… There is no Buddha, no Dharma, no training and no realization…’ When he spoke of ‘affection’ as ‘thuds’ felt in the spot where the thymus gland is located, we related it to Sri Ramana’s declaration that the ‘true heart’ is located on the right side of the chest. Likewise we sometimes connected his radical statements to certain expressions or declarations in the Avadhuta Gita, Ashtavakra Gita, the Upanishads and Zen Koans, or compared them with the teachings of J. Krishnamurti, Nisargadatta Maharaj and even the post-modern ‘deconstructionists’. We could go on thus, making such connections and comparisons, but that did not help us to get a handle on the mystery that was UG!

That mystery, that enigma, is no more. Once, a couple of years back, when Mahesh Bhatt had asked him, ‘UG, how would you like to be remembered?’ UG had said, ‘After I am dead and gone, nothing of me must remain inside of you or outside of you. I can certainly do a lot to see that no establishment or institution of any kind mushrooms around me whilst I am alive. But how do I stop all you guys from enshrining me in your brains?’