Valentine de Kerven

It was January 20, 1991. That night Valentine died suddenly. She simply dropped off while she was sitting in a chair eating her dinner. The houselights were shining brightly. The light of Valentine, however, which had been shining brightly in our Poornakutee in Bangalore, went out permanently. Just the day before, my wife Suguna had gone to Bapatla after she had heard of the news of her brother’s death. She had been quite distressed at the prospect of leaving the company of Valentine. She had grown fond of Valentine during the past five years, during which time Valentine became like a small baby in the cradle. The lives of our children, Aruna and Archana, were intertwined with Valentine’s, as they had known her ever since they were little. They had played games and sang songs to her while she sat in her chair. They teased her and argued with her. As soon as they came home from school they would hug her and shower her with kisses. How could the children bear this sudden death while they couldn’t even imagine living in her absence?

Unfortunately, I wasn’t present when Valentine died that night. Just about an hour and half before her death, I had to go out on an errand. When I left I told her in English that I would be returning soon. She tried to smile and held her right hand out as if to shake hands with me. That once strong hand which had previously given comfort and solace had now shrivelled. I pressed her hand gently and said, “Au revoir, Valentine.” She replied, “Au revoir,” in a weak voice. That was her last goodbye, her last handshake. All was over by the time I returned home. Those hands had become cold and lifeless. My children and her servants were the only ones present when she closed her eyes forever.

It was pitch dark that night. Valentine’s dead body was in the front room. And I was there, like a zombie, keeping a watch over the corpse on the sofa. The city had quietened down. Everything was still except for the occasional roar of a vehicle rolling down the street. I heard a mild moaning from the next room, which died down after a while.

How could I carry on the next day without Valentine? My brain was getting numb as soon I began to think about it. I felt my stomach turning. I was suffering from some inexpressible anxiety.

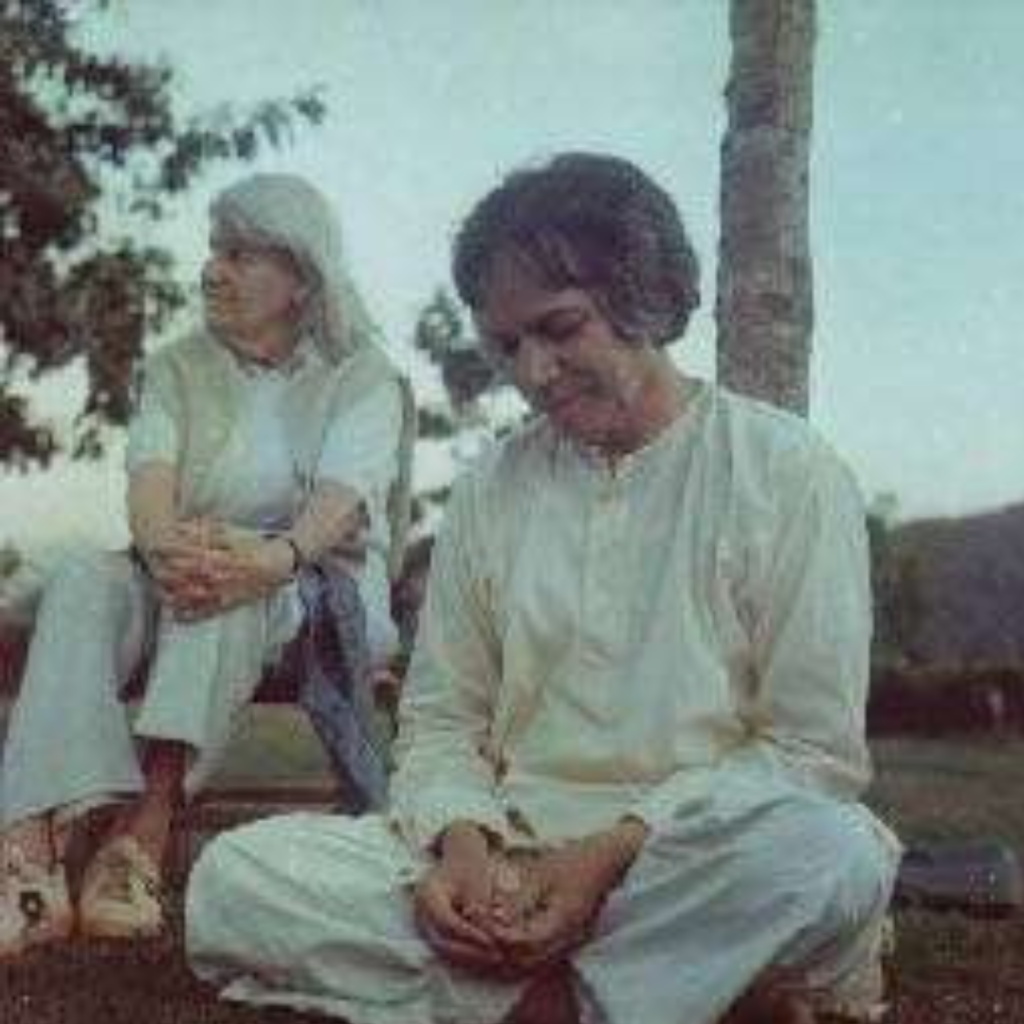

What, indeed, was my connection to her? Who was she? What brought her that great distance, from the place she was born, the Jura mountain region of Switzerland, to Poornakutee in Bangalore, the place where she died? Who was she? Who were we? Who was U.G.Krishnamurti?

It was 30 years ago when an anonymous person who lost all his roots and bearings, and who was roaming in foreign countries like a vagabond, was blown into the Indian Consulate Office in Geneva. Valentine sponsored him with her generosity and handed over to him all she had without a second thought. It was a new turn in U.G.Krishnamurti’s life. Who of us had ever dreamt that a person like Valentine would live her last days and die from Alzheimer’s disease right before our eyes in Bangalore? In her years of stay here, our neighbor had also become involved with Valentine. How could I console them? What should I say to comfort them? I was reminded of the mocking voice of Chalam in a letter he wrote to me many years ago, “Am I still in that lowly state of pining after those who are dead?” I laughed apathetically. This had to be my plight. My mind was to be ripped apart over and over again. Valentine lay still over there, as if she was sleeping.

“The body is a fortuitous concourse of atoms. There is no death for the body, only an exchange of atoms. Their changing places and taking different forms is what we call ‘death’. It’s a process that restores the energy level in nature that has gone down. In reality, nothing is born and nothing is dead,” I was recalling U.G.Krishnamurti’s words with Valentine’s dead body before me. The mind was in no state to contemplate philosophy or science. As ocean waves break upon rocks, all my thoughts were being shattered within myself – I was frozen with the weight of my sorrow.

Suddenly the telephone rang, breaking the silence in the hall. It was U.G.Krishnamurti’s voice on the other end. He was calling from California. There was no emotion in his voice even when he learned of Valentine’s death. He reminded me of the important things I had to do: “Valentine is a foreigner. That’s why you should inform the police of her death. They may give you trouble if you don’t. You must also inform the Swiss Embassy. When will Suguna return?” I said, “She may be returning by tomorrow afternoon. I will wait till she comes back.” “All right. Cremate the body in the corporation crematorium. Valentine never believed in the

rituals performed after death. She was born a Christian, but she never attended the Church even once,” U.G.Krishnamurti said. There was a moment of silence. U.G.Krishnamurti again asked, “What will you do with the ashes after the cremation?

“I will immerse them in the Western section of the river Kaveri near Srirangapatnam,” came the spontaneous from myself. U.G.Krishnamurti was laughing mildly. There was pity in that laughter for the sentiments I couldn’t free myself from.

* * *

Some days later, in the morning, Archana was peering from behind me at the papers I was writing on and asked, “Are you writing the biography of Valentine, Daddy?” I nodded ‘Yes’ and looked into her face. The shadows of memories of Valentine flashed in her facial expressions. I think her greatness would not have been any the less if Valentine had never met U.G.Krishnamurti U.G. does not exaggerate it when he says, “In fact, Valentine’s life story is more interesting than mine.”

When asked to talk about her life, Valentine rarely opened her mouth. Nevertheless, I gathered many details – some were extracted out of her, some were from what I collected from U.G.Krishnamurti who old them to me according to what her sisters had narrated about her to him. I will briefly relate what I know of Valentine’s wonderful life by piecing together all these various details. Valentine’s full name was Valentine de Kerven. She was born in the beginning of the 20th century, on August 1, 1901, in a village called La Chaux de Fond in the Zura mountain region of Switzerland. It is noteworthy that that day is the National [independence] Day of the Swiss people. That might be why Valentine was so fond of her freedom. Valentine’s father, Alfred de Kerven, was well known in those times as a great brain surgeon. His books were translated into almost all the important languages of the world. As he was the one who thoroughly researched a certain glandular disease of the neck, this disorder, the De KervenSyndrome, mentioned in current medical textbooks, was named after him. Valentine was the second of his three daughters. Valentine had an unusual personality even as a child. She never believed anything blindly. She had to find things out for herself and act accordingly. She thus developed her artistic tastes and ideas of freedom. When she was 18, she decided to leave home and move to Paris. She wanted to mould her life in her own fashion by mingling with the artists of that time. But no one in her family liked her plan. When they all tried to prevent her from carrying it out, her father stopped them:

“Don’t force her. We all know what she is like. If we come in the way of her freedom, there is a risk of her leaving us forever. Let her go wherever she wants to go.” He persuaded them, and they bade her farewell. He arranged for a yearly income of 2,000 francs wherever she lived. Valentine never forgot her father’s generosity. She indeed loved him deeply. Even after she had

married, she was reluctant to adopt her husband’s family name, contrary to the custom there. She insisted on keeping her maiden name. Even when she lost her memory because of Alzheimer’s disease while she was under our care, her face would shine with joy whenever there was a mention of her father or she saw a photograph of him.

Valentine’s big eyes always shone. There was some intense light in her eyes. I believe that no one could express herself with her facial expressions and eyes as well as Valentine could. Even when her body withered away in her last days, the shine in her eyes never went down. Valentine was an artist from birth. Combined with her free and defiant spirit, her artistic tastes took peculiar forms after she arrived in Paris. Her interest in drama enabled her to become intimate with many prominent artists in the modern arts theatre of that time. Antonin Artaud was a great poet and philosopher as well as a playwright. Spectators crowded to watch his plays, but knowing his eccentricity they always kept a respectable distance from him. Valentine was one of the select few who came close to him. Valentine used to produce in Paris, along with another artist called Dullin, plays written by Artaud. She did her own designing of the costumes for the plays. The new designs for the dresses she had created earned her a notable reputation in Paris, the centre of fashions, as an apparel designer. Valentine loved photography. She practised it as an art. It did not take long for her to enter filmdom. She was more interested in cinematography rather than acting in movies. She founded de Kerven Films and produced a variety of documentaries. The film she made on the life of the Gypsies earned her a reputation as a prominent director. To settle down in life was repugnant to Valentine. That might have been why she was attracted to the life of the Gypsies, which involved living without security, and in different places, as long as one pleased, and being jovial like a stream. The famous film institute called Gomo British Theatres showed her documentary in all European countries. She also made documentaries about the medical researches of her father.

When she started coming to India with U.G., Valentine would observe with interest the movie industry in India. She watched some Telugu movies in Madras. In her opinion, Bhanumati was an unsurpassed artist in south Indian movies. According to Valentine, she was quite unique in her acting skill. At the time of her stay in Paris, Valentine met a Swiss man called Walmar Schwab. As he and Valentine were of one mind, they worked together amid the artistic and cultural areas of Paris. Gradually, their friendship turned into romance. But she turned down the idea of marriage when it was mentioned, due to her independent spirit. Swiss women are by nature quite tradition˚bound. Revolutionary ideas and independent spirit are scarce among them. It is perhaps hard to believe that until recently Swiss women had no voting rights.Strangely, it was the women in that country who led a movement against their own rights. Valentine was unique in the sense that, although born in such a country, she had very independent ideas, and was interested in free living within her own life.

Although she never participated in any women’s movements, her own life, from the beginning to the end, seemed like a liberation movement in its own right. Valentine never wanted to marry. She detested the institution of marriage. She wondered why a woman should become subservient to man’s authority, and why men and women shouldn’t live together without marrying. When she wore pants in Paris, the centre of fashion, women would throw rotten eggs at her. As her lover had respect for her independent ideas, they lived together without marrying for 20 years, until the Second World War. Schwab had not had much schooling in his youth. So, when he was 40, he wanted to get some education. Valentine encouraged him, and gave him whatever support he needed so he could go to school. He was eventually awarded a doctorate in chemistry, but because he was over˚aged, no one gave him a job. Meanwhile, the Second World War broke out. Valentine and Schwab escaped from Paris and took shelter in Switzerland in an attempt to avoid the Nazis. The laws in Switzerland were very strict at that time: it was a crime, according to Swiss law, to live together without marrying. When the Swiss police learned that the couple was unmarried, they went after them. Valentine and Schwab ran into trouble trying to avoid the police, and had to change their residence several times. They sometimes hid in potato storehouses. At last, unable to bear the pressure of the police chase, they both decided to flee the country and get married. Although they had already lived together for 20 years, Valentine still felt that marriage was bondage. Just to prove her independence from the institution of marriage and authority of man, she prepared a marriage contract. According to that contract, although they were husband and wife legally, neither of them could exercise any rights or restrictions on the other. They both could feel free to lead their own lives without permission or interference of the other. Their incomes were also kept separate. When they married they both signed the contract.

It was not in Valentine’s blood to lead a life without turbulence. She never liked that sort of uneventful life. She felt that a life without adventure or adversity was not her kind of life. She would compete with teenagers in cross country running competitions. They were tough competitions and involved running uphill for four or five kilometres. Such competitions required her to get a medical certificate saying she had the stamina to run against women far younger than her. In spite of these odds, she got her way and participated in the competitions. Before World War II, Spain was under the dictatorship of General Franco. In those days, when most of Europe was resisting Franco’s aggression, some artists started a movement called the Revolutionary Association of Artists. Valentine joined this movement, along with her friend, and actively participated in its anti˚Franco activities. She even received training, along with other fighters, in the use of firearms. The fact that she, who wouldn’t hurt a fly, became a fighter and took to guns in order to bring down a dictatorship in a neighbouring country indicates how deeply the love of freedom was implanted in her personality. She dreamt of going into Spain with her friend secretly, joining hands with the Republicans there, and fighting against Franco. She had even gotten the necessary false passports ready. But when Schwab backed out at the last minute, she too had to cancel her plans. After the World War started, Valentine also worked in the Red Cross Society. Earlier, she had received training as a nurse. I think that only someone like Valentine can express her talents in multifarious ways – as a fighter, a nurse and an artist.

In 1939, before the onset of World War II, Valentine contemplated the conquest of the Sahara Desert along with her friend. Even today, it is not an easy matter to cross the Sahara Desert on a new motorcycle. Half a century ago, most adventurers would not think of such daring deeds. Except for adventurers who contemplated crossing the English Channel or the Atlantic Ocean, no one would have had the guts to attempt to cross a 3,000-mile desert, finding her way even in the middle of frequently raging desert storms. Valentine had great faith in her powerful 7.5 HP motorcycle. If one were to write an account of how she sat Schwab on the back seat and then travelled day and night for three months in the desolate, terrible desert under the hot sun and in the hot winds, this account would be more interesting than a Jules Verne novel. The struggles they went through getting supplies and gasoline for the motorcycle, the meals they ate sitting on the cadavers of camels because they couldn’t set their feet on the burning sand, the hospitality of the residents in the occasional desert villages – adventures of this sort can only be told by a person such as Valentine.

The album of photos that she assembled still remains with us as a witness of their Sahara conquest. Weekly magazines at that time gave high praise for their adventurous journey.

After the World War, in 1954, Valentine contemplated another adventure. This time she travelled to India from Switzerland with her friend Schwab in her Volkswagen car. She came to India for the first time via Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. She and Schwab drove across India, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, in their car. It may be from this trip that she developed, unbeknown to herself, a deep attachment to India. Indian people, especially people from small villages with their simple living, interested Valentine very much. She was so fascinated by the Indian sleeping cot, with woven twine, that she had one transported, along with her Volkswagen, on a boat from Ceylon to Switzerland. She used the cot for a long time after she returned to her country. After she returned from India, Valentine accepted a job in the Indian Consulate in Geneva as a translator. It was about that time that she severed her relationship with Schwab. Valentine never had any children, even though she lived 20 years of her life with him as an unmarried companion before their marriage, along with 20 more years after marriage. Meanwhile, an 18˚year-old lady had come between them. It was such an unexpected and sudden development that the 60˚year-old Schwab fell in love with this woman and began a relationship with her. In the light of her own marriage contract, although she couldn’t find any fault with her husband, Valentine could not swallow the harsh truth of losing someone whom she thought was her own. That is why later, whenever a discussion about woman˚man relationships came up, Valentine would say, “As long as there is a tendency among men and women to own each other, no matter how sweet the relationship is, it will have to turn bitter. No matter how many ideals you cite, and no matter what you do, that tendency will not go away. If the lives of married couples are horrible, the lives of unmarried couples are even more horrible.” At that time Valentine was living in a house given to her by her father. Valentine could not tolerate Schwab carrying on an affair with his new girlfriend. When, not stopping with that, Schwab went ahead and filed a lawsuit in court asking for a divorce from her, Valentine’s mind was closed to him. At the time of the verdict, the judge read their marriage contract and asked in shock, “What kind of a marriage is this? How could you call this sort of a contract marriage? With such a marriage, why would you still need a divorce?” He immediately annulled their marriage and sent them off.

“I never saw Valentine shedding tear.

She had the courage to face any kind of hardship,” says U.G. “The word ‘sentiment’ does not exist in her vocabulary.” After the 40-year–old relationship with her companion broke up, Valentine felt that her life was in vain. What must she do? Why

should she live? She was crestfallen, unable to find any use or aim for her life. One midnight, unable to sleep, Valentine sat on the banks of Lake Geneva. For one who had never cared about her future before, now it seemed terrible. When she told me much later about the mental agony she had experienced that night, U.G. was with us. U.G. asked, looking at Valentine mischievously, “You didn’t feel like jumping into the lake?

She replied, “No use jumping into the water. I knew how to swim.” U.G. later joked about her saying, “She must have been afraid that the water in the lake would be frozen from the cold. Or else she would have jumped in it.

She seemed to have been fated to return home that night without attempting anything drastic on herself, and it was the very next day that U.G. stepped into the office of the Indian Consulate. The lifelines of those two seemed to have merged on that day and started to move in the same direction: they both had not the faintest idea of how they were going to live, what their future was, or why they should live. And both their lives were like kites cast off to the winds of fate.

* * *

Who cares about Valentine now? She never even cared about herself. Even when others reminded her of her adventures and sacrifices, she would smile as though they were quite ordinary. Valentine had no more interest in her own extraordinary personality than the interest a flower has in its own fragrance. Even those who knew U.G. intimately knew her only as a companion to him in his world travels, and as an extraordinarily generous person who made it possible for U.G. to stay in Switzerland. But who knew of the heights of her magnanimity? Ever since the time of the Calamity, U.G. and Valentine would come to India every winter. U.G. would say, “We are migratory birds: we come to this country to escape the winter in Switzerland. Here, unlike in that country, we can find all our conveniences. There is no other higher purpose in coming here.” Valentine always liked to travel to India, and particularly to visit Bangalore. She enjoyed spending her time in Bangalore standing in the upstairs balcony of the house and watching the huge peepul tree in front of the Anjaneya temple. She would watch the large bats that hung on its branches upside down and made screeching noises, as well as the ladies who circumambulated around the statues of snakes installed at the bottom of the tree. Also, there were the lazy buffaloes chewing their cud and swatting themselves with their tails, and the vendors selling a variety of wares from their pushcarts on the street. Everyday she would go enthusiastically half a dozen times to the nearby Gandhi Bazaar to buy something there. Until she was past 80, she would go around alone in the vicinity of Basavangudi in Bangalore. Valentine had the habit of walking fast. At times, I myself found it difficult to catch up with her. When one of us tried to hold her hand to be sure that she would cross the street safely at the crossroads, she would shake our hand off and walk aways wiftly. Everyday in the evenings many friends would gather to talk to U.G. Usually the conversation turned around trivialities. If there were any serious discussions with U.G., Valentine never moved out of the room. She would sit there for hours and listen to the conversations with keen attention. I asked her once, “For how many years have you been listening to U.G.? Don’t you get tired of it?” She would reply, “No matter how many times I’ve heard him, each time it seems new.” Valentine would cook for U.G. while they were in Switzerland. Even there she enjoyed walking several times from their home on top of a hill, about a hundred feet high from the street level, to the marketplace, going with ease down and back up the narrow pathways, on the pretext of needing to buy things. In Bangalore, in the house where we lived, children would gather around Valentine. She would be nice to them and pass out food. Children played with her and sang songs to her. She would clapwith them in joy, even though she did not understand their songs. Aruna and Archana felt great pleasure in spending time with her. They would bring their friends and introduce them to her proudly and showed her off to them. It was Valentine’s habit to say “Voila” for “All right”. When she rolled her eyes and nodded her head while looking at the children, saying, “Voila”, they would join her by singing, “Voila, voila, voila, voila, Valentine.” She too would burst out laughing along with them. The children liked to make her say their names. They would have great fun when she had trouble pronouncing their names. Valentine had other close friends in Bangalore: the squirrels which jumped off from the coconut tree to the balcony and came close to her, the stray street dogs that approached her when she walked on the street fast, the baby monkeys saying ‘Hello’ from the peepul tree across the street from the temple, the lambs nibbling grass in the park – Valentine was great friends with all of them. She took photographs of each of them and preserved them carefully. When she made a photograph, even the ugly face of a baby donkey would look like the face of a royal horse. Once she took me upstairs, offering to show me something interesting. She took me to her table and silently signalled me to be quiet. After a little while, she very gently pulled the drawer open and asked me to peep in. There didn’t seem to be anything in there except rubbish. When I looked in more closely, there were four dark mice moving around. Their mother, sitting in their midst, lifted her head and looked at me fearlessly. In her look I could see the confidence she had that as long as she had the protection of Valentine no one could harm her family. Valentine closed the drawer quietly and said looking at me, “Aren’t they cute?” I can still remember clearly the glee of joy I saw in her eyes. She was quite preoccupied with that family of mice, as though feeding them breadcrumbs and cookies and protecting them from the cat that came to say ‘Hello’ to her were her life aims

By nature, Valentine was not very talkative. She could communicate much better with her eyes and facial expressions than with words. She knew several languages. Her mother tongue was French. She also knew English, German, Spanish and Italian well. After coming to India she learned a few Hindi words. When I sang poems that I wrote about U.G. in Telugu, I could see her feeling sorry that she wasn’t able to grasp the poems directly in Telugu, rather than in my English translation. I felt that I didn’t need any more recognition for my poems than that. Later, she bought the book called Telugu in Thirty Days and tried seriously to learn the language. But she got confused with the Kannada vocabulary that was used around her, and soon quit her effort. Soon after that, Valentine reached a state beyond our words and language, a thoughtfree state where there was no need for words.

By nature, Valentine was not very talkative. She could communicate much better with her eyes and facial expressions than with words. She knew several languages. Her mother tongue was French. She also knew English, German, Spanish and Italian well. After coming to India she learned a few Hindi words. When I sang poems that I wrote about U.G. in Telugu, I could see her feeling sorry that she wasn’t able to grasp the poems directly in Telugu, rather than in my English translation. I felt that I didn’t need any more recognition for my poems than that. Later, she bought the book called Telugu in Thirty Days and tried seriously to learn the language. But she got confused with the Kannada vocabulary that was used around her, and soon quit her effort. Soon after that, Valentine reached a state beyond our words and language, a thought free state where there was no need for words.

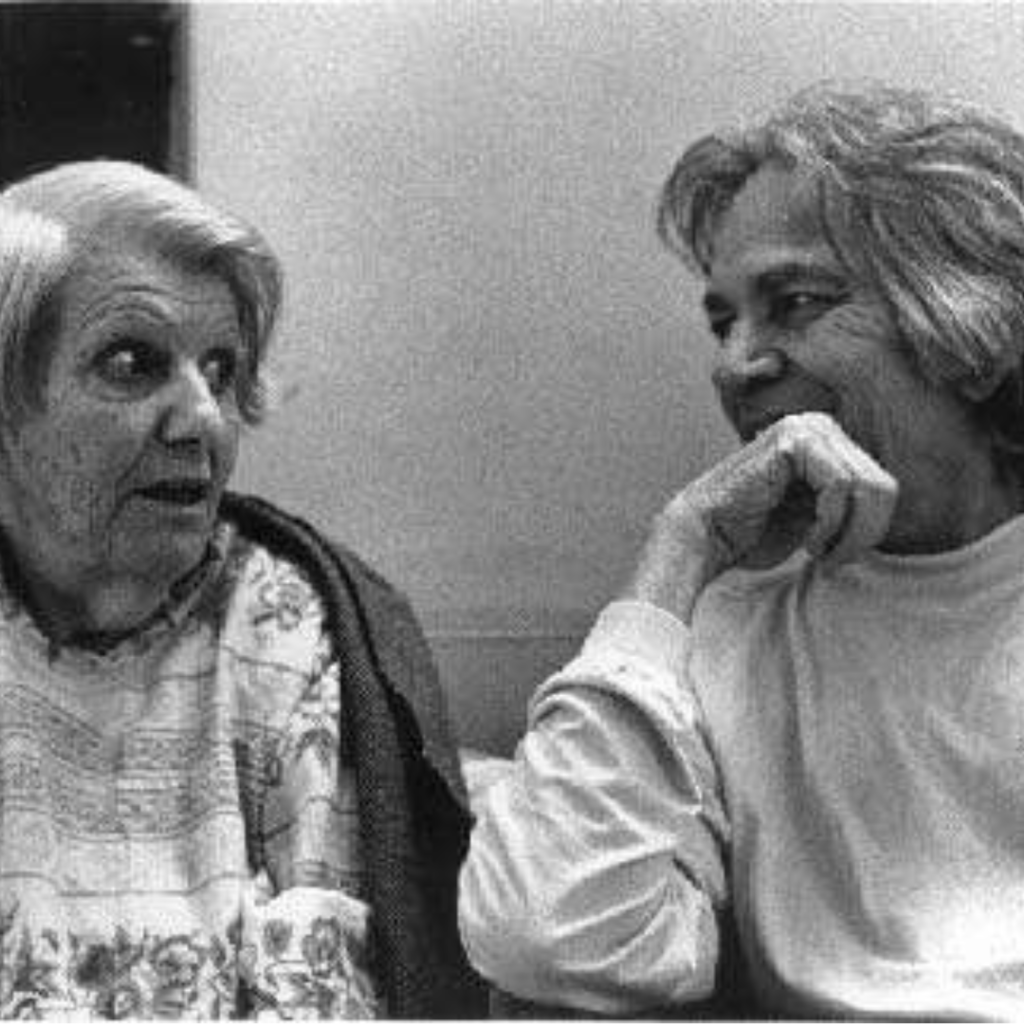

When Valentine was 82 years old, that summer she fell ill for a week in Bombay with sunstroke. From that time, although her physical health recovered, her memory deteriorated day by day. The doctors who examined her in the United States determined that she was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Medical experts are now of the opinion that the disease is spreading worldwide without regard to young or old. Scientists are still unable to fathom this disease, which afflicts memory˚storing neurons in the brain. Here, it’s appropriate to remind ourselves of U.G.’s warning: “Man’s brain is intended to run efficiently this machine called the body. If the brain is used for any other purpose, mankind cannot but be subject to the horrible disease called Alzheimer’s. It’s not cancer or AIDS that will wipe out mankind which has appeared on the earth as a scourge among living species; Alzheimer’s disease is soon going to spread like an epidemic.” With her memory loss Valentine also became less active. That’s when U.G.’s troubles started. It was not easy for him to take her along on his travels. Sometimes an American friend called Kim Lawrence would take care of Valentine’s needs and go around the world with both of them. For some days, famous movie star Parveen Babi also served Valentine while she was travelling with U.G. But as Valentine grew older, and as her Alzheimer’s disease was advancing, it became clear to U.G. that she could no longer travel. He felt that she needed to stay in one place for the rest of her life. It was our sheer good fortune that U.G. decided that Bangalore should be the last stage of Valentine’s life journey and that she should be in our care. It was indeed our good fortune to have been of service to that extraordinary person in her last days. Before he moved Valentine to Bangalore permanently in September 1986, U.G. arranged a get˚together of Valentine with her younger sister Rose and her elder sister Adrian. “Valentine has gone past the stage of being able to travel, and I cannot stop travelling for her sake. So, I am going to make arrangements for her to spend her last days comfortably in India. If you can arrange better facilities for her, I have no objection. I can hand her and her money over to you this instant and go my way,” U.G. said to them. The two sisters declined: “Look at our own state. We ourselves are dependent on others in old˚age homes. What good is our money to us? Valentine is many times more fortunate than us. Who else besides you can look after her better? You do whatever you feel is appropriate, U.G.,” they said and bid Valentine a final goodbye. Later, a year before Valentine died, her younger sister, and then, a year after she died, her elder sister, died in Switzerland.

* * *

Alzheimer’s disease, which wipes out the self and erodes the ability to recognise things, may be a frightening disease; in Valentine’s case, however, it created situations that were amusing to everyone. The first incident of Valentine’s forgetfulness that perturbed U.G. occurred in Switzerland: that year, as always, Valentine and her sister Adrian were reminiscing about their childhood events. After two or three hours, Valentine suddenly turned towards Adrian and asked her seriously, “By the way, how did you happen to know about my childhood events?” Her sister was shocked: “What do you mean ‘How’? I am your sister!” “How could you be my sister? My sister is with me here. Look!” and she pointed to U.G. No one could say a word. Ever since then such forgetfulness became quite common. On some occasions when she was forgetful, we could not contain our laughter at the timely jokes Valentine would make. When an acquaintance once asked her in the way of greeting, “Who am I Valentine?” Valentine answered, “If you don’t know yourself, how am I to know who you are?” On another occasion, when U.G. said, “If you keep forgetting everyone like this, Valentine, you may finally forget me too.” She replied mischievously, “You deserve that!” We all broke into laughter. Once when U.G. and Valentine were travelling on a bullet train in Japan, suddenly Valentine looked around and wondered, “How come there are so many Japanese in this train?” She calmed down when U.G. explained to her that the reason was because they were in Japan. When she noticed that U.G. continued to talk to some friends even after dark, Valentine would get worried that they might remain there. U.G. explained to her as though she were a child, “They have their own homes, Valentine. They won’t stay here. They will leave after a little while.” Then she asked U.G., “If they all leave, what will happen to them?” Valentine had no real anxiety. No worries. She was always calm. If she became angry, it was just for a moment. Then she would laugh happily like a baby. Sometimes, after she ate her dinner, when someone asked her, “Valentine, have you eaten your dinner yet?” she would reply emphatically, complaining to U.G., “No, they haven’t fed me, yet! They haven’t given me a morsel of food in ten days. They have been starving me,” with conviction, as if she were expecting everyone would believe her. It would be difficult to convince her that she had just eaten a full meal. She would read newspapers holding them upside down. She would try to read them aloud in French, and not being able to make sense of them, she would throw them aside. U.G. used to describe her by saying, “She is in what you would call the state beyond Turiya. There is no state higher than that. If that isn’t the Turiya state, what else is Turiya?” When he asked that question, he didn’t sound like he was joking. In earlier days, Valentine’s forgetfulness caused problems for U.G. Once he took her to the Swiss Passport Office in Berne to get the date of expiration on her passport extended. A couple of other friends accompanied them. When he observed Valentine, the official in the Passport Office grew suspicious and said he wanted to talk to her alone. U.G. tried in vain to explain to him her condition. Having no alternative, they left the room, leaving Valentine alone with the official. The official came out of the room in just a couple of minutes, wiping the sweat off of his pale face. He had extended the duration of her passport, but he said, “You can take her now. I don’t need to see her again.” He reported that he asked her, “Who were all those people who came with you?” and she replied that she didn’t know who they were. When he showed Valentine her passport and asked her, “Whose passport is this?” she apparently replied that she didn’t know. The official was shocked. Then he showed her photograph to Valentine and asked, “Is this your picture?” she answered seriously, “That’s not mine. Do I look like that?” The official got very confused by her answers. What was the relationship between U.G. and Valentine? There is no doubt that this question has bothered many people in different ways. There are friends who have whispered among themselves, “When they both met in Geneva in 1964, Valentine was 63. But her age could not have been a big barrier for a physical relationship.” There are others who gossiped, “If there was no relationship, why would she give away all her property without hesitation?” What’s interesting is that U.G. and Valentine were never concerned about such rumours. However, after the behind˚the˚curtain affairs, the secret romantic adventures of the world famous philosopher J. Krishnamurti, who was reputed to be a world teacher, became public through a recent book, some close friends of U.G. were worried that future generations might misunderstand and gain a mistaken impression of the relationship between U.G. and Valentine. U.G. replied to this worry unperturbed, “Let them misunderstand. What do I care?” Once U.G. went to the Bali islands accompanied by Valentine and Parveen Babi, the Indian film star. Parveen needed a change of weather for health reasons. Everyone knew how even a responsible magazine like India Today reported in big captions that U.G. had been married to Parveen, and that they both had gone to Bali for their honeymoon. When he returned to India from Indonesia, press reporters surrounded U.G. and asked him how true those reports were. Then U.G. replied, “I wish that news were true. What more could an aged person like myself want? What more could I want than a beautiful and famous movie star like Parveen Babi landing in my lap with a lot of money!” The reporters were disappointed at U.G.’s answer. When some of his friends suggested to U.G. that he should sue the India Today, U.G. smiled and brushed the idea aside by saying, “If what they wrote was false, it doesn’t bother me. And if it were true, I still am not bothered.” Valentine was never concerned about the rumours that speculated about a relationship between U.G. and herself who was already 60 to 70 years old, nor was she annoyed by people’s curiosity about the nature of her relationship with U.G. When asked at different times about why was it that, on the very first day of meeting U.G. she was so mesmerised by U.G. that she deposited 20,000 dollars in a bank in his name, Valentine would answer with silence. How can a mind that insists on believing blindly that for every action of ours there must be a motive accept the idea that there can be actions without motives? U.G. has said that there can be a true relationship between men and women only when there is no sexual involvement. In our experience it seems only the relationship between a mother and her children is such a pure relationship. Many believe that the relationship between Valentine and U.G. was such.

When U.G.’s life was taking a crucial turn, Valentine entered the scene and stood as his support. However, she always knew clearly that U.G. had no need of her, and she knew that at any moment he was capable of dropping her and her money and going his own way. She led her life with U.G. in a precarious fashion, a life that could be described in India as: “Within every day lurks a danger, but you live till you’re a hundred anyway,” or living as if “wrestling standing on the edge of a knife”. As soon as U.G. took her financial affairs into his own hands, she found no need to continue working at the Indian Consulate. U.G. directed her to sell all the gold she had in her possession, the antique art pieces she ha d inherited from her father, as well as other valuables, so as to convert these items into cash. He then arranged, on the basis of that cash, a fixed monthly income sufficient for Valentine’s needs. In addition, she also received additional money in the form of a pension from her erstwhile job. With that limited income Valentine and U.G. financed their living in the Saanen area of the Alps mountains. U.G., when talking about the intermingling of their lives, has said: “Ever since she met me, Valentine has had no life of her own as such. She has pretty much led my life.”